02 Sep 2025 | Noelle M.K.Y. Kahanu & Nicholas Thomas

In conversation with the curators of "Fault Lines" (Part 1/4): Noelle M.K.Y. Kahanu

The exhibition Fault Lines: Imagining Indigenous Futures for Colonial Collections, supported by this ERC Starting Grant, opened in December 2024 and will run until December 2025 at the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (MAA), Cambridge. A collective, convened by Noelle M.K.Y. Kahanu with Leah-Lui Chivizhe, Taloi Havini and Jordan Wilson, curated this exhibition. In this blog series, they outline the project through responses to questions prepared by Nicholas Thomas, director of MAA. All parts will appear jointly in a publication that is currently in progress. Read the conversations here in advance.

Noelle M.K.Y. Kahanu

Could you introduce yourself and say something about the place and context you are working from? What are the core issues or priorities that shape your work as an artist / curator / activist / researcher and that you have brought to this particular project?

Aloha nō. My name is Noelle Maile Kaluhea Yayoi Kahanu, and I was born, raised, and educated in Hawaiʻi. My Hawaiian name, Maile Kaluhea, came to my great-grandmother in the form of a night dream, an inoa pō. The family gathered in the cottage behind Kaumakapili Church, where she spoke in Hawaiian, sharing her dream of the five maile sisters, all named for various types of an Indigenous vine. My Japanese mother was given the choice among the five possibilities, and she chose Maile Kaluhea, meaning the fragrant maile. I open with this naming introduction because it speaks to the complexity of contemporary Indigenous lives. It speaks to what is generated from the night but is brought forth in the day. I am multi-bodied, formed from islands across oceans, shaped by genealogies, histories, various communities, and the many positions I have held over these many decades. Imbedded in this story is also the concept of duality and balance, positive and negative, night and day, male and female, Native and Non-Native.

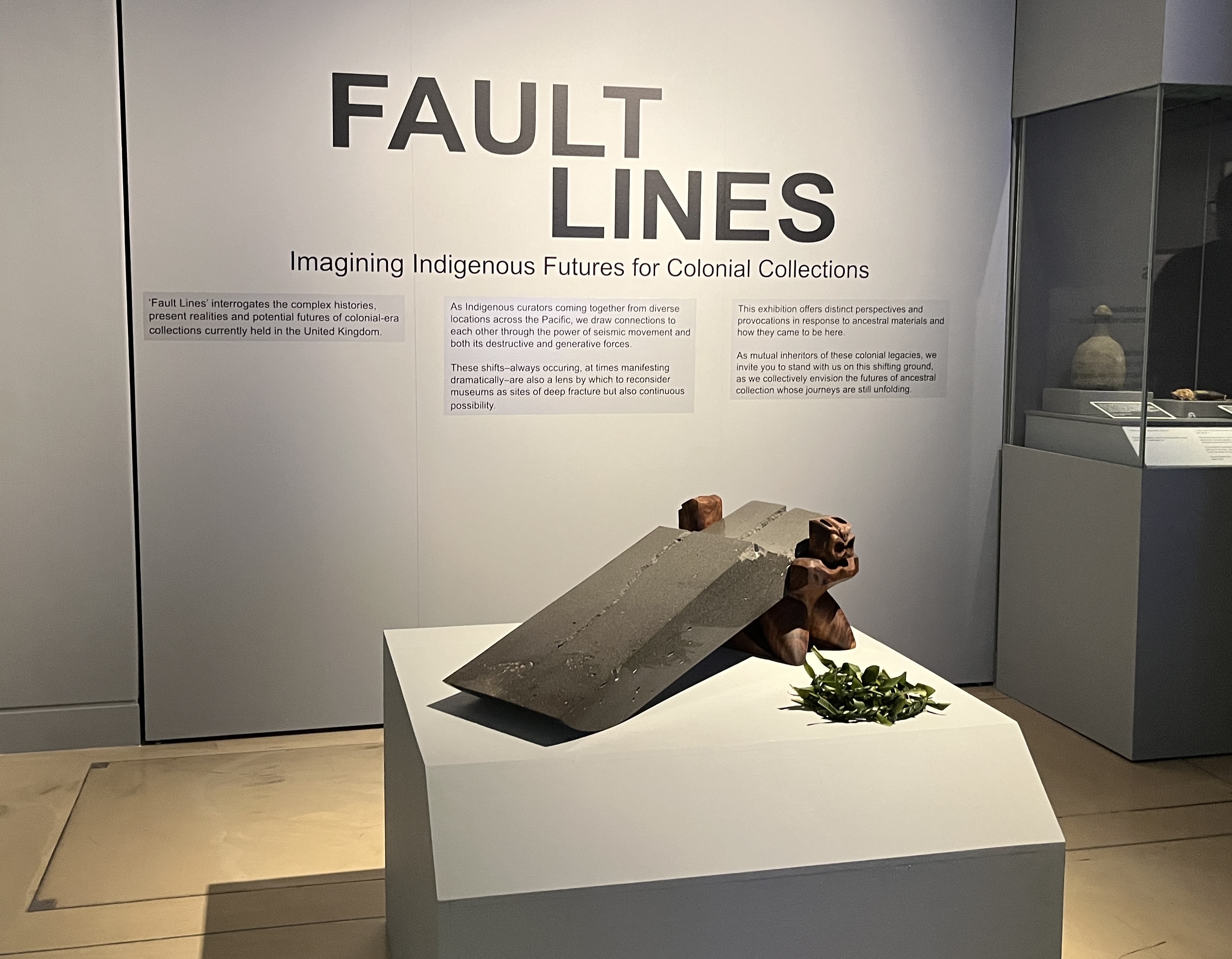

This fundamental Hawaiian philosophy of dualism is also found in Kunāne Wootonʻs contribution to Fault Lines, a carved basalt koʻi or adze, fractured, yet held together by two kiʻi (images/figures) that carry the weight of the koʻi on their backs. It is both an homage to male and female forms that bring life, but also Pele, who brings forth from the cracks in the earth’s surface new land, “following an endless ritual of birth, destruction and rebirth.” In my museum work, I see in these metaphorical fractures the potentiality for new beginnings and new directions that we might not even have imagined.

Fault Lines addresses the future of colonial-era collections in museums such as the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. Could you give us a sense of your engagement with museum collections, and particularly with museum collections such as those in Europe, that are now and have been for decades, if not longer, distant from communities of origin? What in other words are your starting points for imagining the future?

For some thirty years now, I have observed museum community relations, through the lens of federal legislation and appropriations, repatriation, exhibitions and renovations, community programming, and teaching in the field of museum studies. As I grew, so did the field, often so slow that it was imperceptible, other times in a burst of glorious activity. Through Bishop Museum, I have had the benefit of engaging in such key moments - from the renovation of Hawaiian Hall (2009) to the coming together of the last three Kū temple images (2010) to the return of Kalaniʻopuʻuʻs ʻahuʻula (feather cloak) and mahiole (feather helmet) in 2016. As someone who does not have a PhD in the arts and humanities (rather, I have a law degree), I might otherwise have been institutionally side-lined, but fifteen years at Bishop Museum taught me that the most important acceptance came from the collections themselves and the community. All else became a navigation, an understanding that my kuleana (responsiblity) to facilitate the development of relationships between our ancestral mea makamae and their contemporary descendants, to ensure that museums are welcoming places for Indigenous communities, and that museum/community relations shift from “ceding” authority to “seeding” authority, restoring our collective humanity in the process. Eventually, my focus expanded beyond Hawaiʻi to include those collections that came from afar.

Kanaka ʻŌiwi artist Kunāne Wooton’s ʻAuamo no ka ʻUlu explores the exhibition concept of Fault Lines, with its split basalt adze held together by two ki’i, or figures. Photo: Noelle Kahanu.

Kanaka ʻŌiwi artist Kunāne Wooton’s ʻAuamo no ka ʻUlu explores the exhibition concept of Fault Lines, with its split basalt adze held together by two ki’i, or figures. Photo: Noelle Kahanu.

I am in debt to Edward Halealoha Ayau and Hui Malama I Na Kupuna o Hawaiʻi Nei for their training and their steadfast insistence that all ancestral remains and their belongings must return home in order for our foundation to be restored. One of the many lessons I learned was balance, the ceremonial necessity for the presence of both pō (night/darkness) and ao (day/light). Over time, I learned that these negotiations between museums and communities need not be hostile, that there is shared humanity in this process of restoring dignity to those who were so violently disturbed from their long sleep, and that participatory engagement and pilina (the development of relationships) is essential to both short term and long terms gains. It is vital that we call each other by name, share meals, know each other’s families, and tend to these relational intimacies as a meaningful manifestation of aloha. That we do these things, he alo a he alo, face-to-face, is in some ways a reflection of how some mea makamae started on their long journeys. Centuries ago, encounters led to exchanges, gifts, even thefts and wrongful takings, and repatriations or restitutions happening today are not in spite of this past, but adds layers upon it. Entanglements indeed (Thomas 1991)!

Philosophically, I have been very influenced by Māori scholar Paul Tapsell, who envisioned that from the moment of departure of a taonga (treasure), their homeward trajectory was inevitable. I tie the gravitational strength of their return to the ways in which the community “calls” these mea makamae (literally precious things) home and acknowledge the way these ancestral images remove obstacles and participate in their homecoming. Importantly, many museums also have come to view themselves as not merely mausoleums where treasures go to spend the remainder of their years, but rather as weigh stations, stopping points along an ancestor’s extended time line.

But my most recent realization is that we as a community have to be worthy of their return. The challenge for us is to understand the nature of their homecoming. What must we do differently? What higher frequency must we attune ourselves to? Everything happens for a reason, for a purpose, not kapulu (messy) or by accident. Indeed, we find ourselves on our own homeward trajectory, led across the sky by our mea makamae, bound to their remembrances and memories of a world long gone, bringing fresh eyes to old ideas.

When the opportunity arose, what artefacts and/or images from the historic collections (at MAA or otherwise in the UK) were you concerned to foreground? What particular significance does the material have?

Who does not love ʻahuʻula? Exquisite feathered capes and cloaks that offered both physical beauty and spiritual protection; that embodied the love and respect of the generations who collected, cleaned, processed materials, creating a foundation of ʻolonā netting upon which were fastened millions of feathers. How the vast majority of these ʻahuʻula, the epitome of ancestral mana, ended up largely in Europe, is a fascinating subject, but in truth, each has their own moʻolelo, their own story and journey, from makers to owners and beyond. For many, this history remains in obscurity, when provenance records reveal little except a donor’s name. I felt that by looking at two very different ʻahuʻula, one in the Pitt Rivers Museum (PRM), Oxford, and one in MAA, I could revel in the complexities of their histories/non-histories as a reflection of museum community relations.

Kanaka ʻŌiwi conservator-in-training Hattie K.N. Hapai works alongside master Maori textile conservator Rangituatahi Te Kanawa on an ʻahuʻula from the Pitt Rivers Museum, July 2024. Photo: Noelle Kahanu.

Kanaka ʻŌiwi conservator-in-training Hattie K.N. Hapai works alongside master Maori textile conservator Rangituatahi Te Kanawa on an ʻahuʻula from the Pitt Rivers Museum, July 2024. Photo: Noelle Kahanu.

While I often prefer to think about an ʻahuʻula’s origins, in this instance, I was more interested in what happened to them since being in the care of their respective institutions. I use this term “care” loosely because it can mean many things, from physical to spiritual to relational. What does “care” mean and under whose terms? What happens if “care” from a community standpoint and from a museum one is at odds? For Fault Lines, I juxtaposed two feather capes, one which had been displayed at Pitt Rivers sideways for decades, and one which MAA had rarely placed on exhibition.

What approach did you take to contextualising and/or re-activating the material?

I appreciate that Fault Lines provided an impetus for an important intervention, namely the nearly immediate removal of the “sideways cape” from display at Pitt Rivers. This occurred for two reasons: (1) the receptiveness of PRM to my cultural and ethical concerns regarding its display, and (2) the request to loan the cape for exhibition at MAA. As the latter required a conservation assessment, I further suggested that Indigenous conservators (one established & one in training) be brought in to do this work -- an opportunity that rarely exists. Māori textile conservator Dr Rangituatahi Te Kanawa (Ngāti Maniapoto) and Kanaka ‘Ōiwi/Native Hawaiian conservator-in-training Hattie Keonaona Hāpai spent just under a week caring for it at the PRM conservation lab in the Summer of 2024. They cleaned the feathers and prepared it for a new display mount. PRM staff, such as Jeremy Uden and Faye Belsey, were very welcoming and provided access that truly facilitated an air of trust and mutuality. Surprisingly, the ʻahuʻula, despite its decades being flat mounted at a 90-degree angle, was in beautiful condition. The MAA ʻahuʻula was also in stable condition though not as “pristine” as its PRM counterpart in the sense that it showed greater wear. Rangi and Hattie spend time looking at the cape, as well as others, particularly through a digital microscope. Of particular interest was the netting, and the size and count of the ʻolonā fiber. Again, museum staff were extremely accommodating and helpful.

My intention from the outset was a conversation between the ʻahuʻula. Normally displayed flat, I wanted the capes to be upright, to be shown as if they were in a human body form. I wanted to imagine what the two chiefly wearers might say to one another as they contemplated being so far from home in a foreign land. To this conversation was added a contemporary voice, that of Kapulani Landgraf, one of the most important Kanaka ʻŌiwi artists today. Multi-disciplinary and researched-based, her work has appeared in the Asia Pacific Triennial (2018-2019), the Honolulu Biennial (2019), the Whitney Museum (2024) and the Sharja Biennial (2025). As an educator, administrator, artist and curator, Landgraf is extremely busy and does not accept projects lightly. However, she was both inspired and outraged by the photos I shared with her, especially those of the installation at Pitt Rivers. Her contribution, Hoʻoheihei, is loosely shaped based on a template of the PRM ʻahuʻula and is a contemporary ʻahuʻula made of naʻau (pig gut) with red fishhooks and headless nails. Says Landgraf: “When our kūpuna leave our lands (for whatever reason), we expect for them to be cared for, respected and honored as if they would if they were home. Uwē ka pahu hoʻouluʻai i ka pūhā o loko (It is the hollow inside that gives the pahu of growth its cry). The pahu continually resounds, listen...kau ʻeliʻeli kau mai, kau ʻeliʻeli ē...”

This cry, this uwē, brings us back full circle to reflecting on notions of care. For Landgraf, it is our ancestral collections that cry from afar, and the loudness of their sounding is in proportion to the lack of care they receive. To this, I would add my own reflection -- that they cry for our own lack of discernment, our own inability to recognize their needs, wants and desires. There are so many barriers for Hawaiians to visit European collections, the least of which is money, but it should not be the kuleana of the many to find these ancestral treasures. It can remain in the handful of a few, provided that this information is shared, that transparency is created, that relationships and pilina are built with museums that house these collections, and that relationships are facilitated between these ancestral mea makamae and their contemporary descendants. Fault Lines is a truly important way of realising these objectives.

_____________

References

Thomas, Nicholas. 1991. Entangled objects: Exchange, material culture and colonialism in the Pacific. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

The conversations with Leah Lui-Chivizhe, Taloi Havini and Jordan Wilson will be published in the following months. In the meantime, learn more about the research project.