30 Apr 2025 | Julia Siebert

From archival clues to digital maps: Reflections on reconstructing the route of the II. Freiburg Moluccan Expedition

Over the past few weeks, in my position as a student assistant for the research project Markus Mailopu and the ‘II. Freiburg Moluccan Expedition,' I have been working to reconstruct and reassemble the route of the II. Freiburg Moluccan Expedition. This effort led to a digital exhibition that is now part of the Mailopu Archive.

Initially, the results of my research were not intended for publication, rather, I hoped to gain a better overview and understanding of the expedition and its individual stages. However, the process of reconstructing and reassembling the expedition route turned out to be more realizable than initially expected. Additionally, I became determined to reconstruct the route as accurately as possible. Finally, with Knight Lab[1] – a platform offering digital storytelling tools – I found a way to digitally visualize the journey of the expedition participants. By using the tool StoryMap, the visualization process became much easier, while also opening new possibilities for publishing these visualizations as part of the Mailopu Archive.

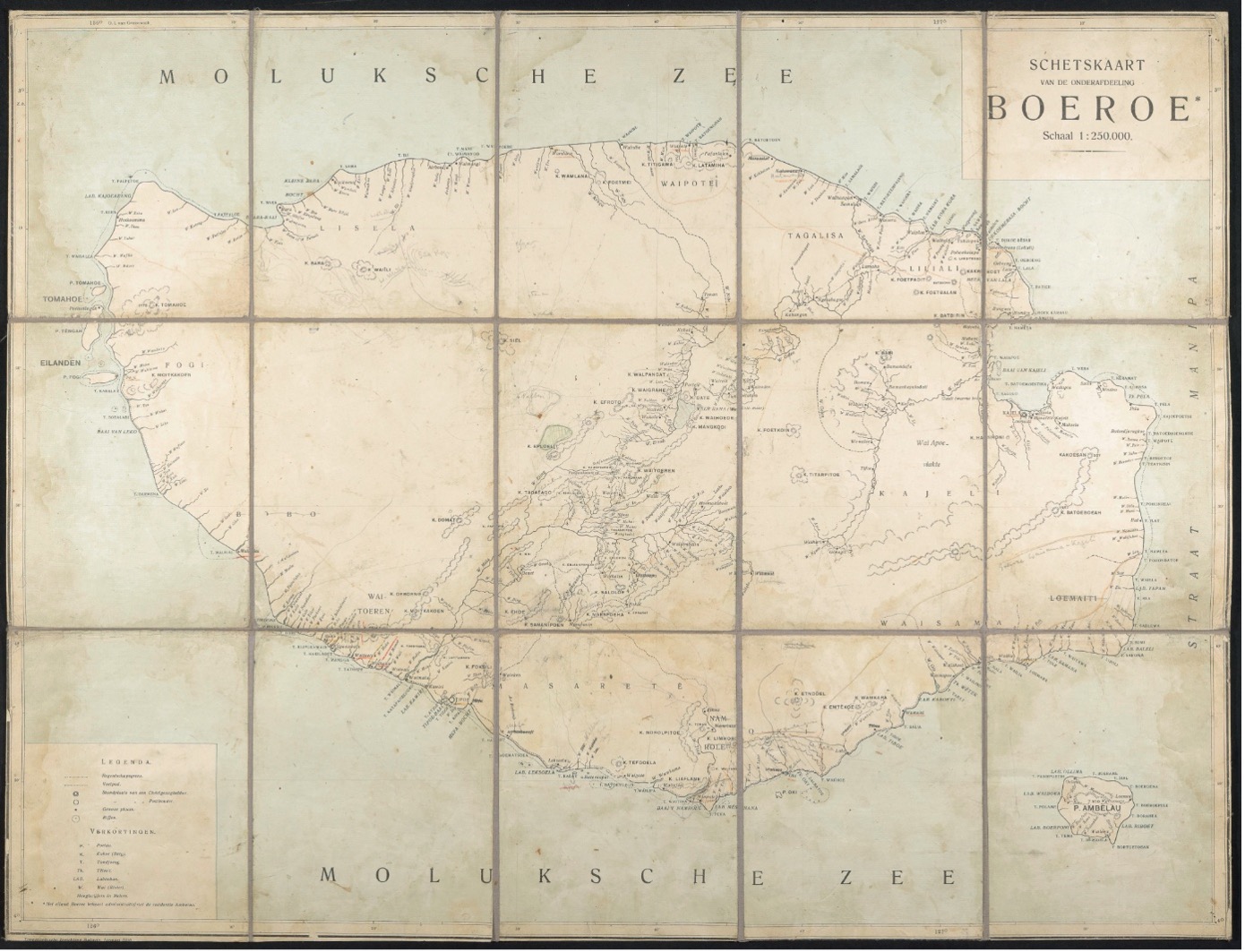

This Dutch map of the island Buru, published by the Topographische Inrichting Batavia in 1910, was used during the expedition, as indicated by hand written remarks. Highlighting the expedition’s contribution to the geographical knowledge of the time, this map proved essential for the reconstruction of their route on Buru. University Archive Munich, Inv. No. NL–75–6.

This Dutch map of the island Buru, published by the Topographische Inrichting Batavia in 1910, was used during the expedition, as indicated by hand written remarks. Highlighting the expedition’s contribution to the geographical knowledge of the time, this map proved essential for the reconstruction of their route on Buru. University Archive Munich, Inv. No. NL–75–6.

A fruitful starting point for my research was the work of Andus Emge, [2] who – together with Erwin Stresemann’s widow Vesta Stresemann – had transcribed diaries, official reports, and correspondence from Erwin Stresemann’s estate at the University Archive of LMU Munich in the early 2000s. In a first step, I read the official reports and took notes whenever the expedition route was mentioned, providing a solid overview of its main stages. From there, I focused on the details of the route, which emerged more clearly through a close reading of the preserved diaries and letters. Whenever my primary source did not provide sufficient detail, I drew upon complementary sources, such as the diaries of Markus Mailopu,[3] which offered valuable insights into the return journey to Germany, a route that had previously been difficult to trace. Another account by Markus Mailopu,[4] describing the ascent of the Kapala Madang mountains on Buru, enabled a more precise reconstruction of the expedition’s route on the island, as the earlier analysis of the primary source had allowed only fragmentary conclusions. Other sources used to reconstruct the route were the diary of Odo Deodatus I. Tauern[5] – especially with regard to his stay on Misool – as well as publications by the expedition members in Petermann's Mitteilungen.[6] Through reading and comparing these various forms of written historical materials created by the members of the expedition, I was gradually able to reconstruct and reassemble the route’s individual segments.

Along this process I have faced several difficulties. Most notably, the expedition members rarely mentioned the exact route, and the specification of locations and dates was often missing in the available historical materials. As a result, my preliminary findings were often fragmentary, and the obtained route fragments had to be reassembled step by step. Another challenge can be traced back to the fact that some of the place names noted in the historical records have changed since the expedition took place or might now refer to entirely different locations. Hence, I was not able to find these places on current maps which further complicated the work of re-construction.

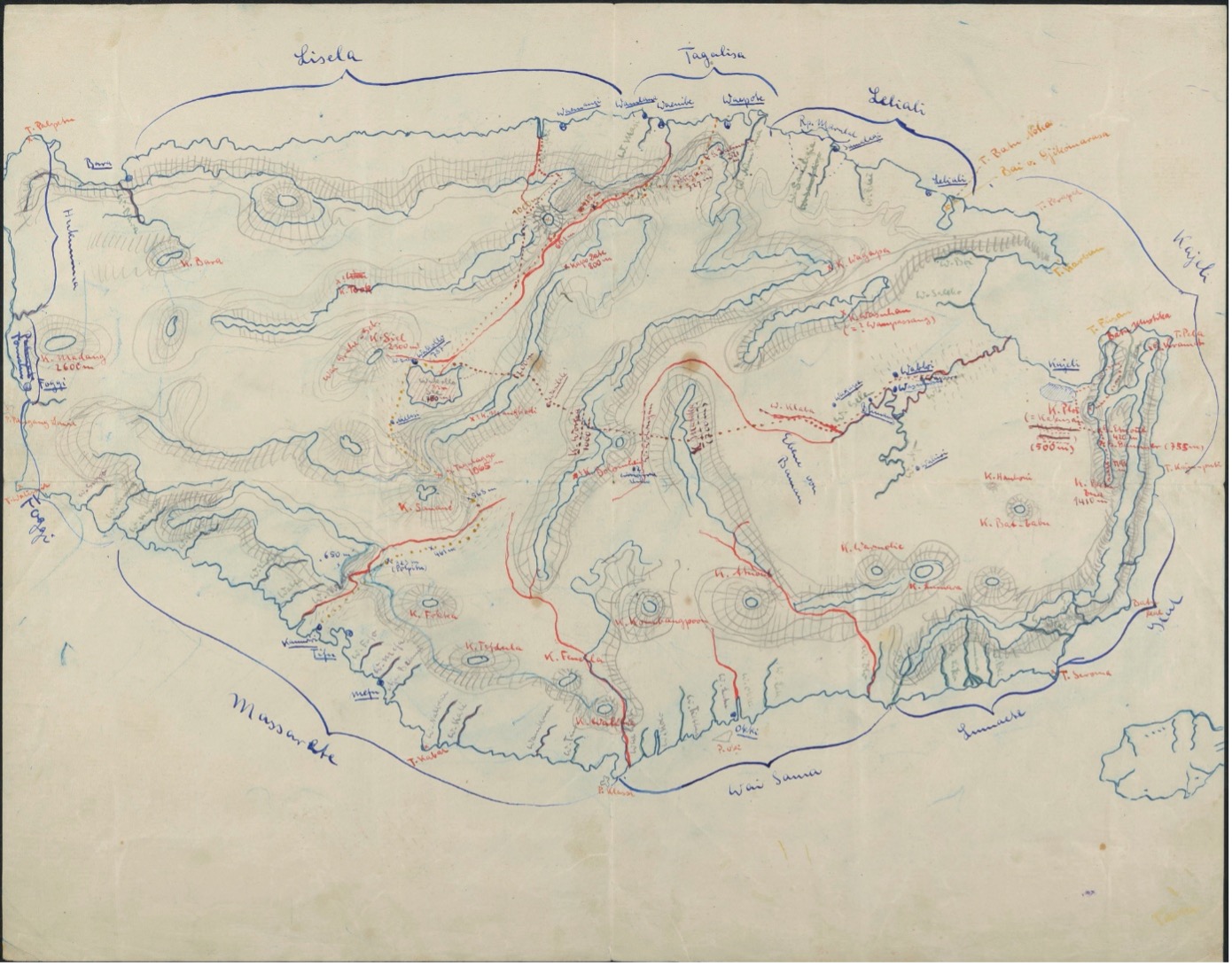

This topographic map of Buru was hand-drawn by Karl Deninger and/or Erwin Stresemann. In the process of reconstructing the expedition route, it complemented the information drawn from the Dutch map shown above. University Archive Munich, Inv. No. NL–75–5.

This topographic map of Buru was hand-drawn by Karl Deninger and/or Erwin Stresemann. In the process of reconstructing the expedition route, it complemented the information drawn from the Dutch map shown above. University Archive Munich, Inv. No. NL–75–5.

A true game-changer solving the majority of the described issues and helping me to successfully reconstruct most of the expedition route were historical maps[7] that were used and created by the members of the expedition. The consideration of historical maps significantly improved my understanding of both the written records and the route itself: Location details from the written historical records that were unidentifiable on current maps could finally be pinpointed by using historical cartography. In fact, it was only by comparing the historical maps with the written historical material that I was able to identify certain locations that I had not been able to determine by reading the texts alone. From that point onward, my work was characterized by a constant back-and-forth between reading the texts, cross-referencing them with the historical maps, and often re-reading the text passages in light of new insights gained through cartographic analysis. Despite the impossibility of reconstructing some sections of the expedition route, due to missing pages in diaries or gaps in correspondence, the overall route can now be traced. After reconstructing and reassembling the routes of the individual expedition participants as thoroughly as possible, the final step consisted of transferring the results into Knight Lab's tool StoryMap and embedding the visualization into the digital exhibition.

Beyond the reconstruction of the expedition route, this project also illustrates how – in this case – the historization of archival material benefits from a multimodal approach. By integrating personal accounts, official reports, scientific publications, and historical maps through digital tools, diverse forms of historical knowledge were brought together and effectively applied to the reconstruction process. In this context, the digital visualization should not be understood as a mere illustration of research findings, but rather as an integral part of the research process itself – a medium that enables, shapes, and communicates knowledge. Drawing on "the narrative power of maps,"[8] this endeavor exemplifies how such multimodal knowledge production can take shape in practice. In this case, digital cartographic tools allow fragmented and marginalized knowledge to be reassembled and narrated in new ways.

If you haven't already, visit the digital exhibition here!

_____________

[1] https://knightlab.northwestern.edu/

[2] Emge, Andus, ed. 2004. Erwin Stresemann: Tagebücher, Berichte und Briefwechsel der II. Freiburger Molukken Expedition 1910-1912. Unpublished Manuscript.

[3] Markus Mailopu's brown diary, accessible via The Mailopu Archive

[4] Stresemann, Erwin. 1918. Die Paulohisprache. Ein Beitrag zur Kenntnis der Amboinischen Sprachengruppen. Koninklijk Instituut voor de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde van Ned-Indie.

[5] Odo D. Tauern's expeddition diary, accessible via The Mailopu Archive

[6] Tauern, Odo Deodatus I. 1914. Reisebeobachtungen von der Insel Seran. Dr. A. Petermanns Mitteilungen aus Justus Perthes’s Geographischer Anstalt 60 (II): 75-78.

[7] List of maps used and created by the expedition members:

- Deninger, Karl and/or Erwin Stresemann. 1912. Map of Buru. University Archive Munich, Inv. No. NL–75–5.

- Deninger, Karl, Erwin Stresemann, and Odo Deodatus I.Tauern. 1914. Karte von Mittel-Seran. Dr. A. Petermanns Mitteilungen aus Justus Perthes’s Geographischer Anstalt 60 (II): Pl. 13.

- Deninger, Karl and Odo Deodatus I. Tauern. 1914. Übersichtskarte von Seran. Dr. A. Petermanns Mitteilungen aus Justus Perthes’s Geographischer Anstalt 60 (II): Pl. 9.

- Deninger, Karl. 1915. Der westliche Teil von Seran. Dr. A. Petermanns Mitteilungen aus Justus Perthes’s Geographischer Anstalt 61: Pl. 50.

- Topographische Inrichting Batavia, 1910. Schetskaart van de onderafdeeling Boeroe. University Archive Munich, Inv. No. NL–75–6.

- Tauern, Odo Deodatus I. 1915. Die Molukkeninsel Misol. Dr. A. Petermanns Mitteilungen aus Justus Perthes’s Geographischer Anstalt 61: Pl. 41.

[8] Caquard, Sébastien, and Wiliam Cartwright. Narrative Cartography: From Mapping Stories to the Narrative of Maps and Mapping. Cartographic Journals 51 (2): 101-106.