07 Jul 2025 | Erika de Vivo

Tracing Sámi lives: A critical look at Florence’s ethnological collections

In a narrow street tucked away in the very heart of Florence, not far from the crowded Piazza del Duomo, an ancient building bears witness to the intricate relationship between Italy and Sápmi – the land of the Sámi people – in the late 19th century.

The Sámi are recognized as the only Indigenous people of the European continent. They refer to their homeland as Sápmi. This territory spans the central northern regions of the Fennoscandian Peninsula and the Kola Peninsula in the Russian Federation. With the establishment of nation states, the ancestral territories of the Sámi were divided among local powers. The colonization of Sápmi was a gradual process that unfolded in different phases and took various forms across the four state contexts of Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Russia. As a result of colonization, stigmatization, and forced assimilation, many individuals who identify as Sámi today either do not speak or have only a limited knowledge of their ancestral languages. During the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century, researchers and scholars developed an interest in Sámi cultures. This interest often manifested in colonial practices, such as taking anthropometric measurements and acquiring (through more or less legal means) elements of Sámi material culture that were to be exhibited in western museums.

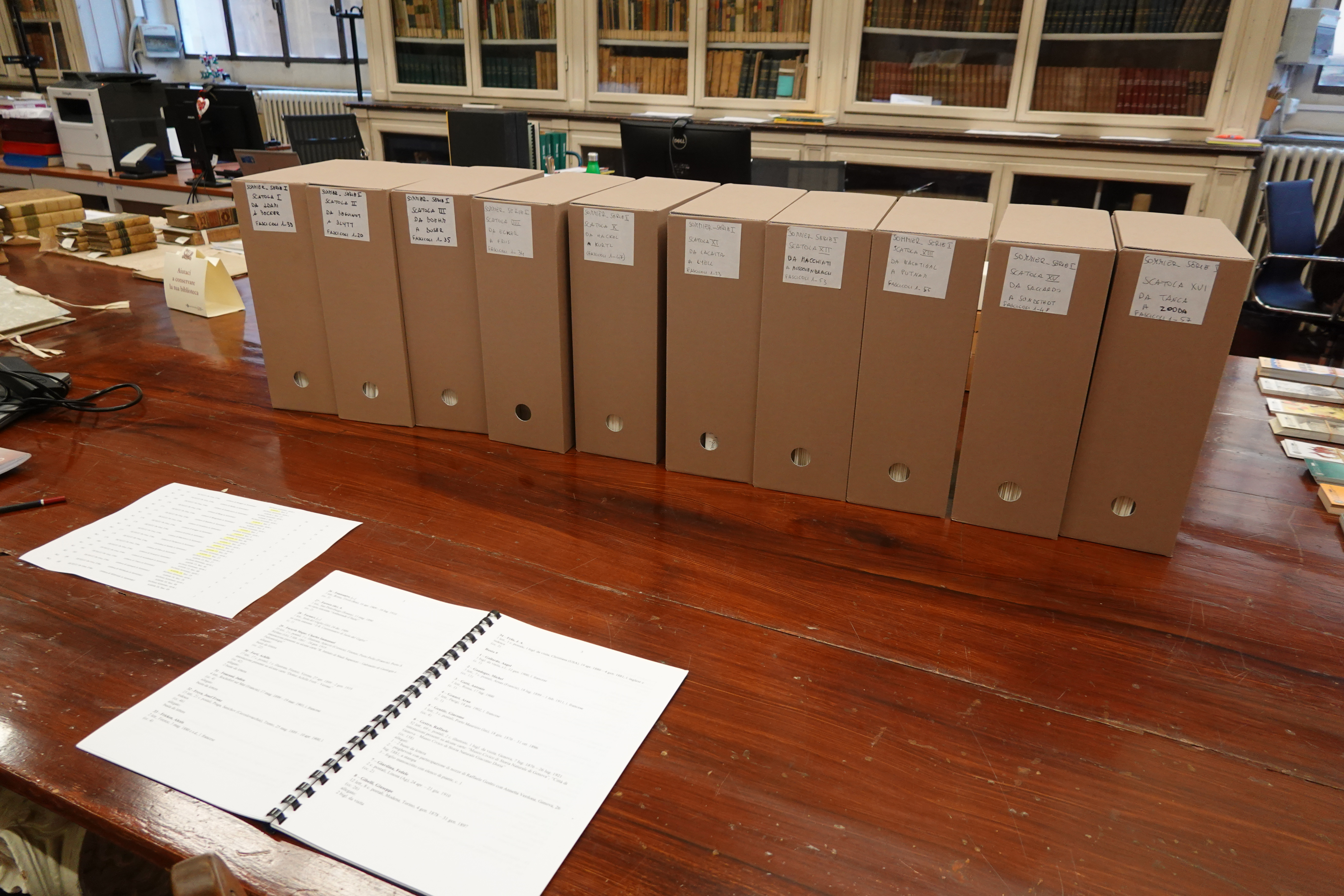

Folders containing the correspondence of Stephen Sommier. Among these letters are numerous epistles addressed to Sommier and focused on Sápmi. These documents are preserved at the Science Library for Botany at the University of Florence. Photo: Erika De Vivo, with thanks to the library for providing access.

Folders containing the correspondence of Stephen Sommier. Among these letters are numerous epistles addressed to Sommier and focused on Sápmi. These documents are preserved at the Science Library for Botany at the University of Florence. Photo: Erika De Vivo, with thanks to the library for providing access.

One of those is located in Florence. In via del Proconsolo, most passersby hardly notice yet another of the city’s imposing 17th-century palaces: Palazzo Nonfinito (literally, "The Unfinished Palace"). Behind its grand wooden gates, this palace houses more than 25,000 ethnological artefacts and thousands of photographs belonging to the Anthropology and Ethnology section of the Museum of the University of Florence, which was founded in 1869 by Italian anthropologist Paolo Mantegazza.[1] The artefacts and photographs displayed in the museum’s exhibition halls and held in its storehouse originate from all over the world and reached Florence through a variety of means. For the communities whose ancestors crafted these artifacts or were portrayed in the pictures, these items serve today not only as painful reminders of unequal power dynamics but also as invaluable reservoirs of knowledge and collective memories. Because of 19th- and early 20th-century collecting practices, the museum has only partial knowledge of the provenance, use, and meaning of many objects in its collections. Mantegazza himself contributed to the collections with ethnographic artefacts he gathered during his fieldwork expeditions. During two expeditions in Sapmi, Mantegazza and the botanist Stephen Sommier amassed a small collection of around 100 Sámi artefacts and a few hundred photographs depicting Sámi individuals. The aim of the two scholars was to provide a comprehensive overview of the livelihood, culture, and physical characteristics of the Sámi people in the late 19th century.

My project, “Locating intergenerational ties: Rematriating late-19th-century unpublished photographs of Sámi women and children" (short LIT)[2], seeks to critically address the work of Sommier and Mantegazza. It acknowledges Sámi people as agents and focuses on Indigenous voices that can be glimpsed between the lines of these scholars’ works. It also sheds light on the intricate interplay between Indigenous agency and colonial power. The main focus of LIT is to bring to light the experiences of six women and three children photographed by foreign researchers between 1879 and 1885. I have chosen to focus on Sámi women and children because they had to endure a double oppression at the hands of male scholars/explorers who embodied the hegemonic colonial society subjugating Sámi people: As Sámi, they were considered inferior to Scandinavian and continental people; as women and children, they were deemed inferior to men. As a result, their voices were silenced by colonial scholars and their experiences marginalized.

Room 6 of the Museum of Anthropology and Ethnology of the University of Florence. In this room, a display case shows some Sámi objects that were collected by Mantegazza and Sommier during their travels in Sápmi between 1879 and 1885. Photo: Erika De Vivo, with thanks to the museum for providing access.

Room 6 of the Museum of Anthropology and Ethnology of the University of Florence. In this room, a display case shows some Sámi objects that were collected by Mantegazza and Sommier during their travels in Sápmi between 1879 and 1885. Photo: Erika De Vivo, with thanks to the museum for providing access.

I have just concluded the first phase of the project, mapping and analyzing the visual, textual, and material elements pertaining to Sápmi currently held in Florence. This three-week archival fieldwork has allowed me to study several of the artefacts collected in both Troms and Finnmark, some of which are mentioned in Mantegazza’s and Sommier’s accounts. I was also able to identify the names of some children and teenagers photographed by Sommier, an important step in reconstructing their life stories. The next phase of LIT will be focused on the identification of their descendants and their communities to begin a collaborative process of reconstructing these children’s life stories.

I shall also focus my attention on the stories behind some of the objects held by the museum. Although little data is currently available for most artefacts collected in Sápmi, traces of their biographies prior to their arrival in Italy can sometimes be found in the diaries and scientific reports of Mantegazza and Sommier. In other cases, signs and letters carved on the artefacts may offer clues on the people who once owned them. After consulting with members of local Sámi communities, I decided to focus on three artefacts: a loom, a giekta (birch cradle), and a belt-pendant which includes two needle cases, a knife, and a pouch.

These artefacts, along with the photographs, serve as tangible connections to Sámi heritage and offer an opportunity to engage in a meaningful dialogue with the descendants of those whose lives and stories they represent. Through this collaborative effort, LIT aims to honor Sámi voices, reclaim silenced histories, and contribute to the ongoing process of cultural rematriation.

_____________

[1] Paul Michael Taylor & Cesare Marino. 2019. PAOLO MANTEGAZZA'S VISION: The Science of Man behind the World's First Museum of Anthropology (Florence, Italy, 1869). Museum Anthropology 42(2): 109-24.

[2] LIT is funded by the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions (MSCA). The host institution is the University Museum of Universitetet i Tromsø - Norges arktiske universitet (UiT) in Tromsø, Norway.

Erika de Vivo is an early career researcher specializing in Sámi studies and critical museology. She is currently a Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions (MSCA) postdoctoral fellow at the University Museum of the University of Tromsø (Norway). Her MSCA focuses on Sámi people’s experiences during colonial encounters in the late 19th century. Her project aims to bring to light the individual life stories of women and children photographed by two Italian anthropologists between 1879 and 1886. In 2023 she completed a 10-month post-doctoral fellowship at the Institute for Advanced Studies in the Humanities (IASH) at the University of Edinburgh, UK. For her PhD in cultural anthropology (University of Turin, 2021), Erika worked on the Márku-Sámi festival Márkomeannu.