29 Nov 2022 | Luisa Marten

Burden or opportunity? Discussion on ‘ethnographic collections’ in German institutions

14 November 2022. The lecture room at the Münchner Volkshochschule (Munich adult education centre) was filled and precisely two minutes before 7 pm the audience turned silent in anticipation. The upcoming panel discussion "Raubkunst-Debatte: Wem gehören die Objekte aus kolonialen Zeiten?“ (“Debate on looted art: Who owns the objects from colonial times?”) was co-hosted by the Museum Fünf Kontinente and sought to shed light on the current discourse about the handling of museum collections with colonial context. The debate has long made its way from cross-disciplinary academia into the general public and by now most Germans have heard about the Humboldt Forum, the so-called Benin bronzes and the discussions about their restitution. The political topicality of this debate and the public interest in its negotiation filled the room with tension. The audience had high expectations towards the four invitees who covered a wide range of perspectives. The hosts allowed for a sincere, intense, and also emotional discussion between the interested audience and the scholars and museum representatives. The discussion covered various questions:

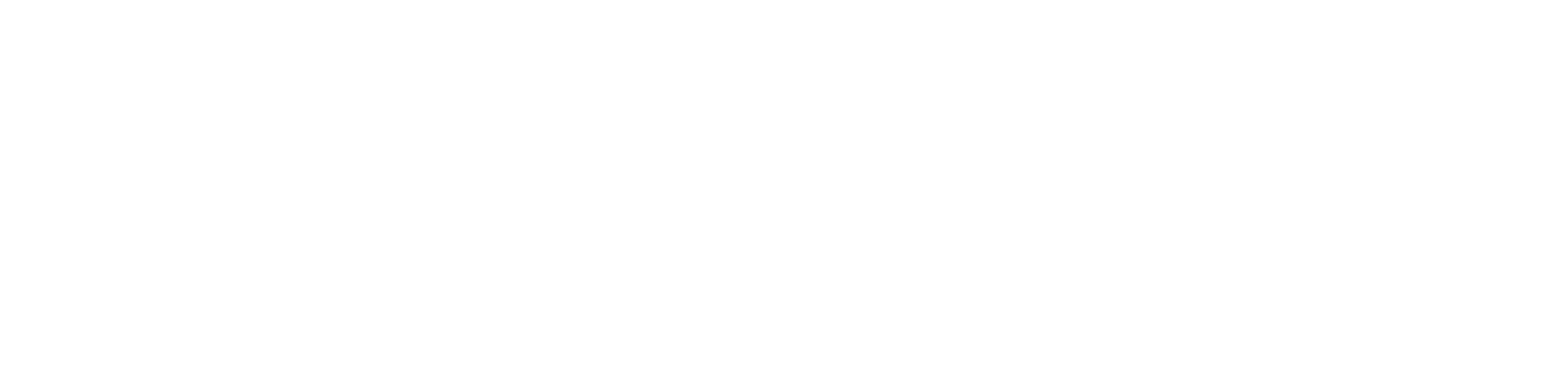

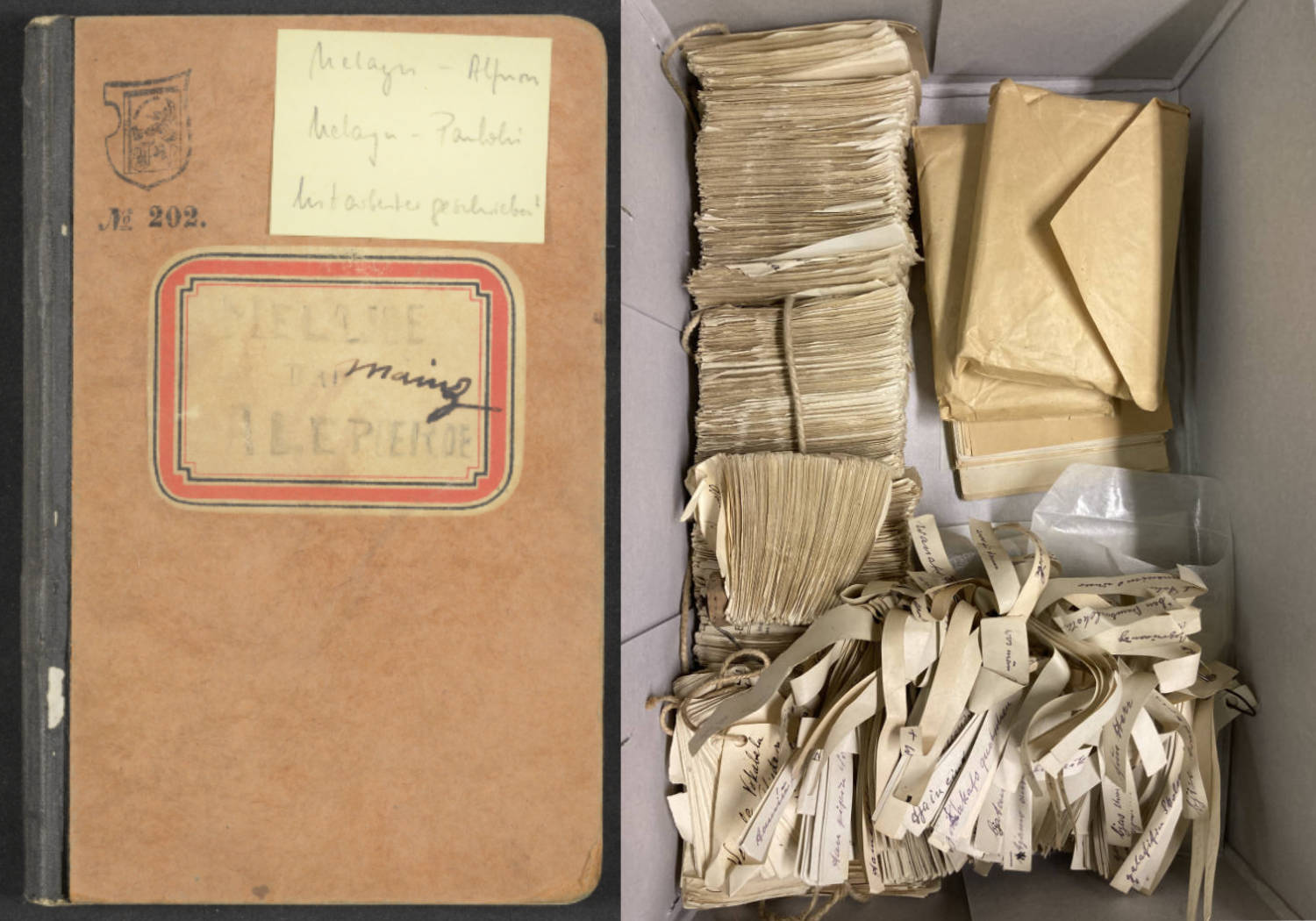

Knowledge production in the early 20th century: This diary (left) was kept by Markus Mailopu, who traveled from his home in the Moluccas to Germany accompanying the II. Freiburg Moluccan expedition, 1910 – 1912. The participating German scientist used index cards (right) to learn Indigenous languages they considered to be vulnerable to extinction. Both stored at the University Archive in Munich.

Knowledge production in the early 20th century: This diary (left) was kept by Markus Mailopu, who traveled from his home in the Moluccas to Germany accompanying the II. Freiburg Moluccan expedition, 1910 – 1912. The participating German scientist used index cards (right) to learn Indigenous languages they considered to be vulnerable to extinction. Both stored at the University Archive in Munich.

Photo: Luisa Marten.

- In which ways is the term ownership conceptualized throughout the discourse?

- For whom and for what purpose do museums keep objects?

- How can they incorporate the results of provenance research into their curatorial practice?

- And how to cooperate with stakeholders from other countries without perpetuating historically grown power dynamics?

At the ground level, these questions do not only concern pieces identified as looted art, but ‘ethnographic collections’ in general. To answer these questions, museums require time, money, and manpower – all of which are scarce.

Mamadou Diawara, one of the speakers, who had arrived from Frankfurt and spoke from an anthropological perspective, acknowledged that this situation might easily seem like a burden. But the complexity of this issue, he argued, could at the same time provide a chance to radically rethink knowledge production in general. Working closely with the objects, analyzing their materiality, usages, journey, historical context and what they tell about the people who created and used them, is what encourages collaborative research – research that is open to the design of joint approaches and works to unravel and process a shared history.

This is where academic research comes into play. Museums should not and cannot be made solely responsible to take up this mammoth task: Working cross-institutionally, -disciplinarily, -culturally and through geographical and temporal constraints lies at the heart of anthropological practice. Furthermore, academic research projects are granted a higher level of creativity and risk taking, not least because they often fly under the radar of public attention.

My research focuses on anthropology’s interlocutors and the complexity of ethnographic knowledge production. I am going to explore an approach that combines archival research, disclosing historical dimensions of today’s dynamics, and contemporary digital technologies which enable collaborative research and are open to Indigenous approaches. This combination will most hopefully provoke not only the processing of dispersed objects and neglected histories, but also the generation of new knowledge and the joint reappraisal of a shared history. As Mamadou Diawara suggested on 14 November in Munich: ‘Ethnographic objects’ in museums and archives are not just a burden but also an opportunity!