31 Jul 2021 | Philomena Luna Härdtlein

Expressing “inner form”: Two moai kavakava in August Macke’s collection of forms

“Man expresses his life in forms. Every art form is an expression of his inner life. The exterior of the art form is its interior.” — August Macke, “The Masks” (1912: 22)1

When I started my historical research on the “early collections” of Rapanui carvings, I was fascinated to discover that two moai kavakava appeared to be connected to the German expressionist August Macke. Both moai kavakava, probably collected at the end of the 18th century, were part of the collection of Munich’s Museum für Völkerkunde (today known as Museum Fünf Kontinente) until 1951, when one figure was given in exchange to the art dealer Arthur Speyer and sold to the Linden-Museum Stuttgart in 1976 (Appel 2021; Menter 2021).

When I first saw the moai kavakava still housed in the Munich museum, I felt touched by the presence of death and a still vivid facial expression sculptured out by the fine lines. I came to understand why August Macke, who was a member of Der Blaue Reiter, used both moai kavakava to think about the “inner form”. The Rapanui carving possibly inspired the artist in a particular way, too.

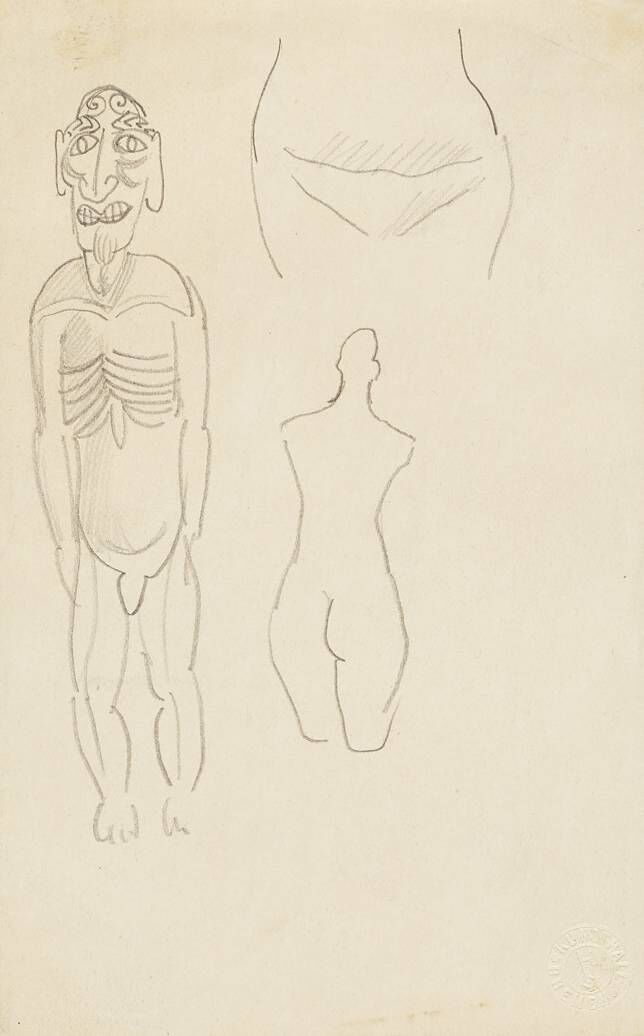

August Macke’s drawing (1913), Kunsthalle Bremen, Inv. No. 1965/473, depicts the moai kavakava, which is currently in Linden-Museum Stuttgart. Photo: kulturgutscanner.

August Macke’s drawing (1913), Kunsthalle Bremen, Inv. No. 1965/473, depicts the moai kavakava, which is currently in Linden-Museum Stuttgart. Photo: kulturgutscanner.

In “The Masks”, Macke’s contribution to the almanac “Der Blaue Reiter” (Macke 1912), a photograph shows a moai kavakava, assumably the same figure currently on display in Museum Fünf Kontinente (Appel 2009: 23f). In the almanac, ethnographic objects, children’s art, folk art and expressionist artworks are juxtaposed in order to develop a supposedly universal language of form (Bujok 2009: 10). The idea of the abstraction of form was described through the expression of the “inner form”. For Macke, “real” art means the expression of intangible ideas and forms — tangible through word, colour and sound, and mediated through the senses and emotion (Macke 1912: 21). Macke’s notion of the “inner form” could be defined as the expression of the innermost idea or spiritual essence materialized in artworks.

While Macke was neither interested in the cultural meaning nor in the origin of the ethnographic objects, he wanted to emphasize the expression of the “inner form” depicting his impression of a moai kavakava in a drawing. He probably used a photograph of the moai kavakava, now at Linden-Museum Stuttgart, as a template for his sketch (Heiderich 2000: 250f). This is particularly evident when you look at the relief carving on the head, posture and the shadow cast.

Capturing and expressing forms of ethnographic objects, as seen in the example of Macke’s drawing and contribution to the almanac, becomes significant for collecting the “inner form”. Macke’s work created a form of artistic collecting that I propose to call “collecting the ‘inner form’”. In the context of our project, then, “collecting form” means “collecting, remembering, and re-enacting Rapanui carvings”.

As August Macke used a photograph of the moai kavakava in Stuttgart for his drawing, Rapanui artists are using the photographs of older carvings because they are dispersed in museum collections. Visiting the Rapanui figure in Munich, like Macke did in 1911 (Heiderich 2000: ibid), I realized that I re-collect Macke’s “collection of forms”. Such a collection could also be of importantance to contemporary Rapanui artists in order to translate the idea of the moai kavakava into new wood carvings — to reinvent, remember and express the inner form.

____________

1 English translation by P. Härdtlein; original quote: “Der Mensch äußert sein Leben in Formen. Jede Kunstform ist Auesserung seines inneren Lebens. Das Auessere der Kunstform ist ihr Inneres.”

References

Appel, Michaela. 2009. Männliche Figur (moai kavakava). In: Elke Bujok et al. (eds.) Der Blaue Reiter und das Münchner Völkerkundemuseum. Munich: Hirmer Publishers, pp. 22–25.

Bujok, Elke. 2009. “Der Blaue Reiter” und die Rezeption ethnographischer Objekte. In: Elke Bujok et al. (eds.) Der Blaue Reiter und das Münchner Völkerkundemuseum. Munich: Hirmer Publishers, pp. 9–14.

Heiderich, Ursula. 2000. “Der Leib ist die Seele”. August Mackes Beitrag zum Almanach Der Blaue Reiter. In: Christine Hopfengart (ed.) Der Blaue Reiter. Kunsthalle Bremen, March – June 2000, exhibition catalogue, pp. 248–254.

Macke, August. 1912. Die Masken. In: Wassiliy Kandinsky & Franz Marc (eds.) Der Blaue Reiter. München: Piper, pp. 20–26.

Correspondences (P. Härdtlein, April – August 2021)

Dr. Michaela Appel, Museum Fünf Kontinente in Munich.

Dr. Ulrich Menter, Linden-Museum Stuttgart.